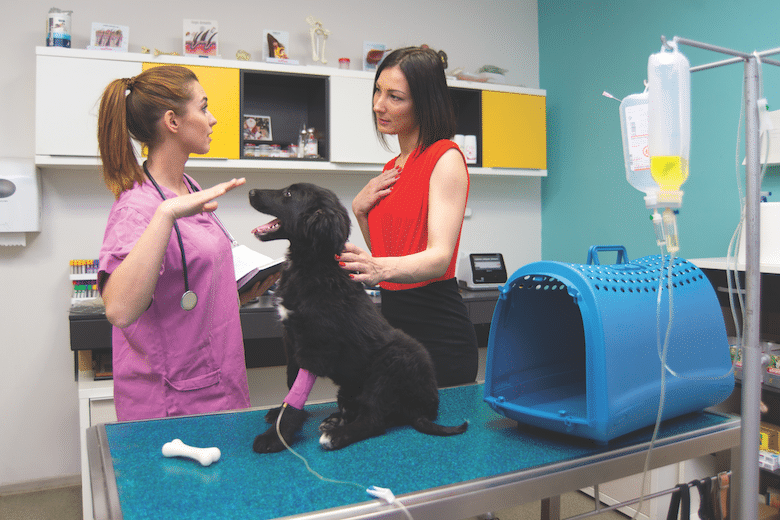

You’re at the vet’s office with your dog, and he needs fluids! While this can be scary to hear, “fluids” are a common treatment for many canine ailments. If you own dogs long enough, chances are that at some point they will receive parenteral fluid therapy. Parenteral refers to administration via a needle into the body, rather than by mouth or other routes.

Fluids are administered for a variety of reasons including during surgery, to treat dehydration, toxicity and shock, and when other systemic illnesses, such as kidney disease, are present.

How fluids work

Fluids are usually given by one of two routes: intravenous/IV (meaning directly into the vein via a catheter) or subcutaneous/SQ (a needle is used to introduce a “bubble” of fluid underneath the skin). Intravenous fluids are immediately beneficial, as they are given right into the bloodstream, while subcutaneous fluids are slowly absorbed over time.

The IV route is used in more serious conditions when immediate hydration is necessary and must be done in the hospital, while subcutaneous fluids are given when rehydration can or needs to be slower. This is usually done on an outpatient basis.

If fluids are given under the skin, the veterinarian will use a needle, gently poke through the skin and administer the fluids. This will lead to a lump on your dog’s back or shoulder area, which will be absorbed over one to eight hours, depending on how dehydrated your dog is.

IV fluids must be administered in the hospital. A catheter is placed in the vein by either the veterinarian or a veterinary technician or assistant. The most commonly used vein is the cephalic, which runs along the top of the foreleg and is generally easily accessible. The saphenous vein in the rear leg can also be used. After the catheter is placed, the IV will be wrapped to prevent it from being pulled out accidentally.

There are several types of fluids including sodium chloride (NaCl), Plasmalyte, Normosol and lactated ringer’s solution (LRS). What type your dog receives depends on the underlying condition and availability at your veterinarian’s office. Complications related to fluid therapy are rare.

Photo: Slavica | Getty Images

Some common reasons a dog will be given fluids

Some common conditions that benefit from fluid therapy include pancreatitis, an inflammatory, painful condition of the digestive tract, and kidney and liver disease. In the summer, overheating and dehydration due to overexertion and water deprivation are sometimes seen. Other common reasons for fluid therapy are:

Prior to and during surgery: Anesthetic gasses and medications can lower blood pressure. IV fluids can help manage this problem and provide increased blood flow to the kidneys. This is especially important in elderly animals or those who have pre-existing kidney disease.

Gastroenteritis: This term describes symptoms ranging from lack of appetite to vomiting and diarrhea. It can be caused by viruses, dietary indiscretion and foreign objects in the stomach and intestines. These can all lead to dehydration, and either SQ or IV fluids are helpful to restore and maintain hydration. In cases of mild gastroenteritis, outpatient treatment is often sufficient, and subcutaneous fluids will be given. In moderate to severe cases, hospitalization and more aggressive IV therapy may be needed.

Toxin ingestion: Dogs are often curious and will follow their noses to just about anything. I have treated dogs who have ingested everything from fiberglass to dark chocolate brownie batter to raw bread dough. Fluids are often a component of treatment for toxin ingestions. They increase blood flow through the kidneys, an effect that is sometimes called “flushing.” This increase in blood flow can be protective for the renal system especially in the face of toxins such as NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen) or antifreeze ingestion.

Fluids are often very helpful for dogs who are ill. While they can seem scary, their beneficial effects generally far outweigh any risks. Always talk with your veterinarian about your concerns.